Holbein's Praise of Folly Pack

- Newt

- Nov 18, 2025

- 2 min read

Holbein the Younger (1497–1543), famed for his portraits and his satirical Dance of Death woodcuts, also lent his hand to the margins of Erasmus’s celebrated text In Praise of Folly (Moriae Encomium). First published in 1511, Erasmus’s witty essay personifies Folly as a woman who praises her own influence over popes, princes, scholars, and common folk alike. It became one of the defining works of Renaissance humanism, mocking vanity and corruption with laughter rather than lament.

Holbein’s contribution came in the form of marginal drawings produced in Basel around 1515. These illustrations are light, playful, and ironic — Folly crowned with a fool’s cap, scholars tangled in their own books, clerics distracted by worldly pleasures. They punctuate Erasmus’s text with visual wit, offering commentary that is at once decorative and satirical.

The images in this pack come from the Victorian Reeves & Turner edition of 1876, which proudly advertised itself as “Illustrated with many curious cuts, Designed, Drawn, and Etched by Hans Holbein.”* Where the Dance of Death pack is stark and admonitory, the Praise of Folly pack is exuberant and comic. To emphasise this contrast, we have made it an all-red-suit deck, using conventional Hearts and Diamonds together with the red Spades and Clubs from our Stroop Effect pattern.

Here are the four kings,

And here are the four aces:

The Wild card shows Erasmus at his desk, writing the opening adress to More

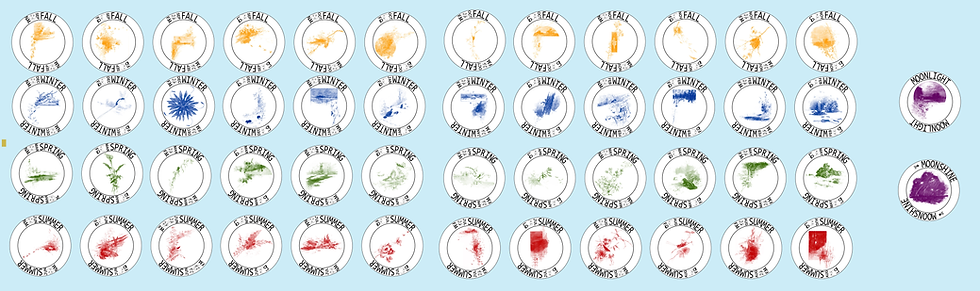

Here is the full set of cards:

The cards appear in the order they did in the original, cycling through the ranks.

If you would like to get a set of our Praise of Folly cards, they are available here, printed on demand, at Make Playing Cards.

You can read about our Dance of Death set here.

And about our Stroop and Hyperstroop decks here.

*In fact, Holbein’s authentic contribution to Praise of Folly was a set of pen-and-ink marginal sketches made around 1515 in Basel, in the copy owned by the scholar Oswald Myconius. These were playful, spontaneous drawings, not formal engravings.

Later, in the late 18th century, the Berlin engraver Johann Gottlieb Friedrich Unger produced a polished set of wood engravings “after Holbein,” based on those Basel marginalia. These engravings circulated widely on the Continent and became the standard visual accompaniment to Erasmus’s satire.

The Reeves & Turner edition reused Unger’s engravings, presenting them to English readers as “Holbein’s cuts.” This is the tradition we have drawn upon for our card pack: the Victorian engraved version of Holbein’s Folly imagery, itself descended from the Basel marginalia.

Comments